by Jack Norris, Registered Dietitian, Executive Director of Vegan Outreach

Contents

- Introduction

- Air Pollution

- Land

- Water

- Grass-Fed Beef and Climate Change

- Summary

- Appendix A: Animal Agriculture’s GHGs

- Appendix B: Reducing U.S. GHGs by Going Vegan

- Bibliography

Introduction

Animal agriculture is one of the most significant contributors to human-made greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution, deforestation, and water use. With so many alternatives available, making choices that help the environment is easier than ever.

For example, the vegan Beyond Meat Burger is nearly identical nutritionally to a beef burger, but its production, packaging, and distribution generates 90% fewer greenhouse gas emissions and requires 46% less energy, 99.5% less water, and 93% less land (Heller and Keoleian, University of Michigan, 2018).

An analysis of United States diets found that compared to the average United States diet, a healthy United States diet, a Mediterranean diet, and a healthy vegetarian diet, a vegan diet has fewer GHG emissions, and less land and water use (Jennings et al., Nutrients, 2023).

An analysis of United Kingdom diets found that compared to lacto-ovo-vegetarian, pescatarian, low-meat, medium-meat, and high-meat diets, a vegan diet has the least negative impact on greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, euthrophication, and biodiversity (Scarborough et al., Nature Food, 2023).

A study comparing Irish dietary patterns of omnivores, flexitarians, pescatarians, vegetarians, and vegans found that a vegan diet produced the fewest GHG emissions and used the least amount of land. Pescatarian diets used slightly less water than a vegan diet, both of which used less than other diets (Burke et al., Environmental Research, 2025).

Even when completely organic, a meat-based diet has a relatively high environmental impact compared to a plant-based diet (Rabes et al., Sustainable Production and Consumption, 2020).

Dairy has a large environmental impact, making lacto-ovo-vegetarian diets less environmentally-friendly than vegan diets and even some low-food chain diets, containing some fish, bivalves, and insects (Kim et al., Global Environmental Change, 2020).

Air Pollution

The air pollution caused by animal agriculture significantly contributes to greenhouse gases. It also leads to premature deaths and intolerable air quality in low-income communities.

Greenhouse Gases

Livestock and animal foods are responsible for 14.5% to 20% of all human-generated greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Appendix A). Limiting global warming to 1.5°C or 2°C will likely require extensive and unprecedented changes to the global food system, including incorporating more plant-based diets (Clark, et al. Science, 2020).

Taking nutrition needs and food production of a country into consideration, vegan diets were determined to provide the lowest per capita greenhouse gas emissions in 97% of 140 countries studied (Kim et al., Global Environmental Change, 2020).

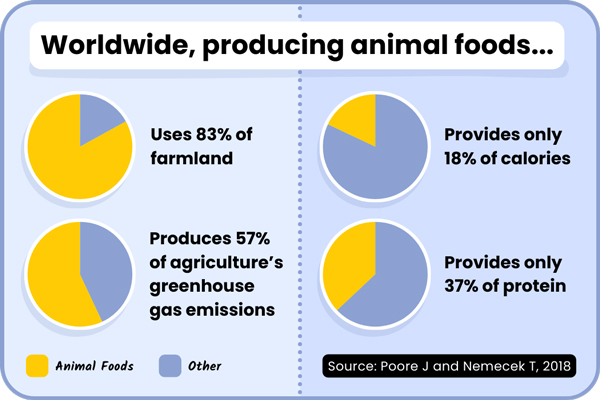

Producing protein from beef emits 90 times the greenhouse gases as an equivalent amount from peas. Even when comparing emissions from the lowest-impact meat and dairy products to the highest-impact plants, plant-based protein sources consistently have a smaller carbon footprint (Ritchie H, Our World in Data, 2020). Meat, dairy, and egg production and aquaculture contributes 56-58% of food’s greenhouse gas emissions while providing only 37% of the protein and 18% of the calories (Poore and Nemecek, Science, 2018).

Fishing is also implicated in climate change. Commercial fishing that uses bottom trawling disturbs carbon stores in the ocean’s floor and significantly contributes to greenhouse gas emissions and ocean acidification (Attwood et al., Frontiers, 2024).

Multiple reports have found that a vegan diet has the most potential for reducing greenhouse gas emissions:

- Worldwide, changing to a vegan diet could reduce agricultural emissions by 84% to 86%. The reduction in air pollution would prevent approximately 236,000 premature deaths per year (Springmann et al., Nature Communications, 2023).

- Land displaced by producing animal foods has the potential to sequester 152.5 gigatons of carbon (GtC) in living plant biomass. Ruminant animal pastures for meat and dairy comprise 72% of the carbon, while cropland for animal feed makes up the other 28%. This amount of carbon represents the past decade of fossil fuel emissions. Researchers consider it comparable to the reductions necessary to limit global warming to 1.5°C (Hayek et al., Nature Sustainability, 2020).

Smaller shifts toward a plant-based diet can also have large impacts on the environment:

- Globally, replacing 50% of animal-sourced foods with plant-based alternatives would reduce agricultural and land use (deforestation) emissions by 31% by 2050, while also increasing food security (Kozicka et al., Nature Communications, 2023).

- A global shift towards a flexitarian diet by 2050 would make it possible to limit global warming to 1.5°C (Humpenöder et al., Science Advances, 2024).

- In the United States, replacing half of all animal-based foods with plant-based foods could reduce about 224 million metric tons of emissions annually by 2030, the same amount as 47.5 million passenger vehicles (Heller et al., Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan, 2020).

In contrast, eating locally does little to change the impact of various diets (Ritchie, 2018).

See Appendix B for a controversy surrounding how much becoming vegan in the United States can reduce GHG emissions.

Degrading the Air Quality of Local Communities

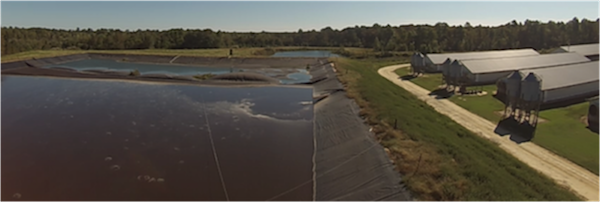

Hog and dairy farms produce enormous waste. It’s stored in lagoons and then sprayed onto fields, destroying the quality of life in local communities.

The Sierra Club quotes residents living near hog waste lagoons:

[Hog waste] comes over here just like it’s raining. That’s what we inhale if we’re outside, and it comes inside the house because you can’t keep that odor out. We don’t have cookouts or family get-togethers like we used to, because we don’t know when the odor is gonna come. When it’s really hot, it burns your eyes.

Land

Meat, dairy, and egg production and aquaculture uses about 83% of the world’s farmland but provides only 37% of the protein and 18% of the calories (Poore and Nemecek, Science, 2018).

In the United States, replacing beef with beans would free up 42% of the cropland (Harwatt et al., Climatic Change, 2017).

An amount of land that can produce 100 g of protein from plants can only produce 60 g from eggs, 50 g from chicken, 25 g from dairy, 10 g from pigs, and 4 g from beef. Replacing all animal-based products with nutritionally comparable plant-based alternatives could feed 350 million additional people in the United States (Shepon et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2018).

We should point out that one study analyzed ten different diet scenarios and found that a lacto-vegetarian diet required the least amount of land, lower even than a vegan diet (Peters et al., Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene, 2016). It’s not clear why. The main difference between the two diets was that they assigned 4 cups of dairy to lacto-vegetarians and 2.9 cups of soymilk to vegans suggesting their model must assign a larger amount of land for producing soymilk than dairy. Vegans don’t typically consume such large amounts of soy milk. More importantly, Our World in Data compared the land use of soymilk to cow’s milk with data from Poore and Nemecek (2018) and found that dairy requires 14 times as much land per volume of milk (Ritchie, 2022).

Water

Globally, a diet that excludes animal products can save 19% of freshwater (Poore and Nemecek, Science, 2018).

In the southwestern United States, the Colorado River is of critical importance for 40 million people but persistent overuse has depleted its reservoirs; of the Colorado River’s direct water consumption, 46% goes to growing hay for cattle (Richter et al., Communications Earth & Environment, 2024).

Using data compiled by Poore and Nemecek (2018), Scarborough et al. (2023) calculated that a vegan in the U.K. will use only 53% of the water used by a meat-eater who eats a medium amount of meat.

Grass-Fed Beef and Climate Change

Most beef cattle in the United States live the last portion of their lives on feedlots where they’re “finished” by eating grains. Although producing feedlot-finished beef emits significantly more greenhouse gases than producing plant foods, it generally emits fewer greenhouse gases than cattle who graze for their entire lives.

But some people argue that, contrary to the idea that grazing cattle harms the environment, it can actually be a solution to climate change. This idea gained momentum with a 2013 TED talk by biologist Allan Savory, How to green the world’s deserts and reverse climate change.

Savory says that land being turned into deserts is one of the greatest promoters of climate change and that the idea that grazing livestock is the leading cause of desertification is misleading. He argues that the only way to combat desertification is to use livestock to mimic the historic herds of wild ruminant animals living and migrating on grasslands.

Savory developed a method for how cattle ranchers could mimic these historical herds and started a movement among ranchers to implement his methods. In his TED talk, he showed images of impressive changes to a number of plots of land that had previously been desertified and said that applying these methods to half the world’s grasslands offers the most hope for solving climate change.

At the end of his talk, Savory receives a standing ovation for the hope he inspires for reversing climate change.

Is Savory correct?

If grazing livestock is going to combat climate change, it must result in a negative amount of CO2-equivalent greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere. It’s difficult to see how this could be the case given that grazing animals releases large amounts of methane (CH4), a form of carbon that is many times more potent than CO2, and the reason why ruminant animals are normally considered to be such a driver of climate change.

Even if methane wasn’t involved, it would be unlikely for grazing animals to remove carbon from the atmosphere. There’s a cycle of carbon being incorporated into plants, then into the animals who eat the plants, then into the humans who eat the animals, and eventually back to plants. During that cycle, carbon leaks into the atmosphere in a variety of ways. Soil carbon sequestration, the permanent storage of carbon in the soil, is the only variable that can overcome carbon leaking in a grazing system. This can happen by the soil trapping more decaying organic matter and feces than it previously had, by grasses growing deeper roots, and by plants that livestock don’t consume being added to the grazing land. (There’s also a nitrogen cycle that impacts climate change and follows a similar pattern as carbon with regard to grass-fed beef.)

How much carbon can be sequestered by the soil by changing the way we graze animals? Extensive research has examined this question and the answer is “not much.”

The Food Climate Research Network of Oxford University published a thorough report on the subject, Grazed and Confused (2017). The report points out that “Ruminants in well-managed grazing systems can sequester carbon in grasslands, such that this sequestration partially or entirely compensates for the CO2, CH4 and N2O these systems generate (Table 1, p. 12).” But there is a significant limiting factor in that only soils that have been relatively depleted of carbon have the potential to sequester significant amounts and once they’re saturated, there becomes little potential to sequester more at which point the grazing animals once again become net-positive carbon emitters.

Grazed and Confused concludes:

This report concludes that grass-fed livestock are not a climate solution. Grazing livestock are net contributors to the climate problem, as are all livestock. Rising animal production and consumption, whatever the farming system and animal type, is causing damaging greenhouse gas release and contributing to changes in land use. Ultimately, if high consuming individuals and countries want to do something positive for the climate, maintaining their current consumption levels but simply switching to grass-fed beef is not a solution. Eating less meat, of all types, is.

Since 2017, much additional research has been published, though it doesn’t change the conclusions of Grazed and Confused.

One study compiled 292 local comparisons of conventional and improved beef production systems across global regions (Cusack et al., Global Change Biology, 2021). They conclude:

Overall, this meta-analysis suggests that substantial GHG emissions reductions are possible in beef production systems, both via increased efficiency and land-based C sequestration….Nonetheless, given the unlikelihood that these strategies will be applied globally to maximum effect, beef management changes for increased efficiency and C sequestration should be considered as complements to efforts to curtail the growing global demand for beef in order to achieve large-scale, sustainable reduction in food GHG emissions.

At current beef consumption levels, a nationwide shift to grass-fed beef in the United States would require 30% more cattle which would have significant environmental impacts. Only reductions in beef consumption can guarantee reductions in the environmental impact of the food system (Hayek and Garrett, Environmental Research Letters, 2018).

In conclusion, under ideal conditions, which usually don’t exist, grass-fed beef can produce fewer emissions than feedlot beef. Under even more ideal conditions, grass-fed beef can sequester carbon for a period of time. But it’s not realistic to think that grass-fed beef can be a solution for climate change, especially compared to being vegan.

Summary

Animal agriculture is not a sustainable system and your environmental footprint can be drastically reduced on a plant-based diet!

Please see our Go Vegan section to learn how you don’t need animal foods to be healthy or to have high-protein, satisfying meals.

Appendix A: Animal Agriculture’s GHGs

The Food and Agriculture Organization (2013) of the United Nations estimates that livestock are responsible for 14.5% of total human-generated GHG emissions. Poore and Nemecek (Science, 2018) estimate that animal foods represent 56% to 58% of food-related emissions, while food represents 26% of total GHG emissions, making animal foods responsible for 15% of total GHG emissions. Twine (Sustainability, 2021) estimates that animal agriculture accounts for a minimum of 16.5% of total GHG emissions. Xu et al. (Nature Food, 2021) estimate that animal foods represent 57% of food-related emissions, while food represents 35% of total GHG emissions, making animal foods responsible for 20% of total GHG emissions.

Appendix B: Reducing U.S. GHGs by Going Vegan

An article in Newsweek (Don’t bother going vegan to save the planet. Do this instead, January 25, 2025), claims that if everyone in the United States went vegan, the country’s greenhouse gas emissions would decrease by only 2.6%.

Newsweek cites What if the United States stopped eating meat? (Clarity and Leadership for Environmental Awareness and Research (CLEAR) Center, UC Davis, December 20, 2020):

In 2017, Professors Mary Beth Hall and Robin White published an article regarding the nutritional and greenhouse gas impacts of removing animals from U.S. agriculture. Imagining for a moment that Americans have eliminated all animal protein from their diets, they concluded such a scenario would lead to a reduction of a mere 2.6 percent in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions throughout the United States.

CLEAR’s description of White and Hall’s analysis is misleading. White and Hall determined the amount of GHG that would be reduced if all animal agriculture was replaced by plant agriculture at agriculture’s full, current capacity. However, if everyone in the United States went vegan, the current amount of agriculture wouldn’t be required to feed the United States population.

Two weeks after running Don’t bother going vegan, Newsweek published Even one person’s food choices affect the whole planet (February 14, 2025), saying:

Frequently, veganism is compared to recycling, as both are seen as individual actions that have limited effects. Building a plant-forward food economy is not, however, structurally comparable to recycling. Recycling is a downstream effort to mitigate the damage of a throwaway society. Veganism is an upstream effort to shrink the size of the animal agriculture industry by reducing demand for its products.

So, how much can going vegan in the United States reduce someone’s carbon footprint?

Eshel et al. estimate that replacing all meat with plant foods in the United States (on a per-protein basis) would result in an almost 40% reduction in dietary and a 5% reduction in overall emissions, but they didn’t include replacing dairy and eggs in their analysis (Scientific Reports, 2019, Figure 2.e).

Poore and Nemecek (Science, 2018) estimate that the United States population becoming vegan could reduce food-related emissions by 77%.

Heller et al. estimate that, in the United States, replacing half of all animal foods with plant foods could result in a 35% decrease in diet-related emissions (Center for Sustainable Systems, University of Michigan, 2020). Doubling that impact by replacing all animal food would decrease diet-related emissions by 70%.

Figure 4 of White and Hall’s paper suggests that a theoretical, plant-only diet produces 70% to 71% lower GHG emissions than the current United States diet.

The Environmental Protection Agency reports that “In 2022, direct greenhouse gas emissions from the agriculture sector accounted for 9.4% of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions.” A 70% to 77% reduction in food-related emissions would result in a 6.6% to 7.2% reduction in total GHG emissions.

To put the potential reductions in context, a March 2023 IPCC report recommends a worldwide reduction in GHG emissions of 43% by 2030 and 84% by 2050 (p. 21, Table SPM.1). In April of 2021, the Biden Administration set a goal for the United States to reduce greenhouse gas pollution by 50% to 52% by 2030.

Hayek (2019) argues that, “Top-down estimates indicate that total US animal methane emissions are 39-90% higher than bottom-up models predict. This implies that animal emissions in the United States, in official reports by government, such as the US EPA, and in numerous peer-reviewed scientific publications, are routinely underestimated.” Bottom-up models are used in estimating agricultural emissions; this likely means that the amount of emissions that can be reduced by going vegan, as discussed in this Appendix, is slightly underestimated.

For the United States to meet these climate goals, most of the emission reductions must come through government policy and industry. But in terms of things the average person can do, switching to a plant-based diet is one of the most impactful.

Bibliography

Eisen MB, Brown PO. Rapid global phaseout of animal agriculture has the potential to stabilize greenhouse gas levels for 30 years and offset 68 percent of CO2 emissions this century. PLOS Climate 2022 1(2): e0000010. Eisen and Brown are associated with Impossible Foods, a company that makes plant-based meats. They found in their analysis that if animal agriculture were phased out over the span of 15 years, greenhouse gas emissions could stabilize for 30 years and offset 68% of carbon dioxide emissions through the remainder of this century. The resulting greenhouse gas reductions would provide half of those necessary to limit global warming to 2°C.

Environmental Protection Agency. Agriculture Sector Emissions. Updated January 16, 2025.

Kozicka M, Havlík P, Valin H, Wollenberg E, Deppermann A, Leclère D, Lauri P, Moses R, Boere E, Frank S, Davis C, Park E, Gurwick N. Feeding climate and biodiversity goals with novel plant-based meat and milk alternatives. Nat Commun. 2023 Sep 12;14(1):5316. Two of the 13 authors had connections to Impossible Foods, a manufacturer of plant-based meats.

Pohl E, Lee SR. Local and Global Public Health and Emissions from Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations in the USA: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2024 Jul 13;21(7):916. Not cited. This review found higher rates of mortality, infant mortality, and respiratory diseases for people living close to factory farms, but the data was all cross-sectional.

Skolnick A. The CAFO Industry’s Impact on the Environment and Public Health. Sierra Club. 2017 Feb.

Springmann M, Clark M, Willett W. Feedlot diet for Americans that results from a misspecified optimization algorithm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018 Feb 20;115(8):E1704-E1705. Not cited. Suggest that White and Hall (2017) may have double-counted the GHG emissions required in producing nitrogen fertilizer for their plants-only analysis.

Tompa O, Lakner Z, Oláh J, Popp J, Kiss A. Is the Sustainable Choice a Healthy Choice?-Water Footprint Consequence of Changing Dietary Patterns. Nutrients. 2020 Aug 25;12(9):2578. Not cited. Modeled the water footprint of various diets based on food intake patterns in Hungary. Found a vegan diet to have the smallest water footprint but considered a vegan diet too impractical due to nutrient inadequacy and cultural acceptability.